Will Sunderland’s lost basketball glory ever return?

Today, the Newcastle Eagles are the most successful franchise in basketball, winning a total of 27 trophies, including clean sweeps in 2006, 2012 and 2015.

However, fans today may be unaware that the team’s roots are actually in Wearside.

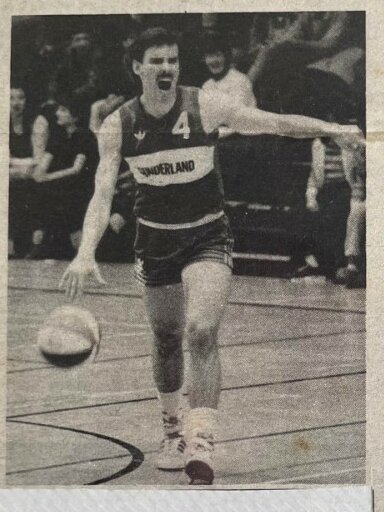

From 1976 to 1995, the team played in Sunderland under various monikers, perhaps best known as the Sunderland Saints during a three-year period at the beginning of the 1980s, which saw the club win two play-offs in 1981 and 1983.

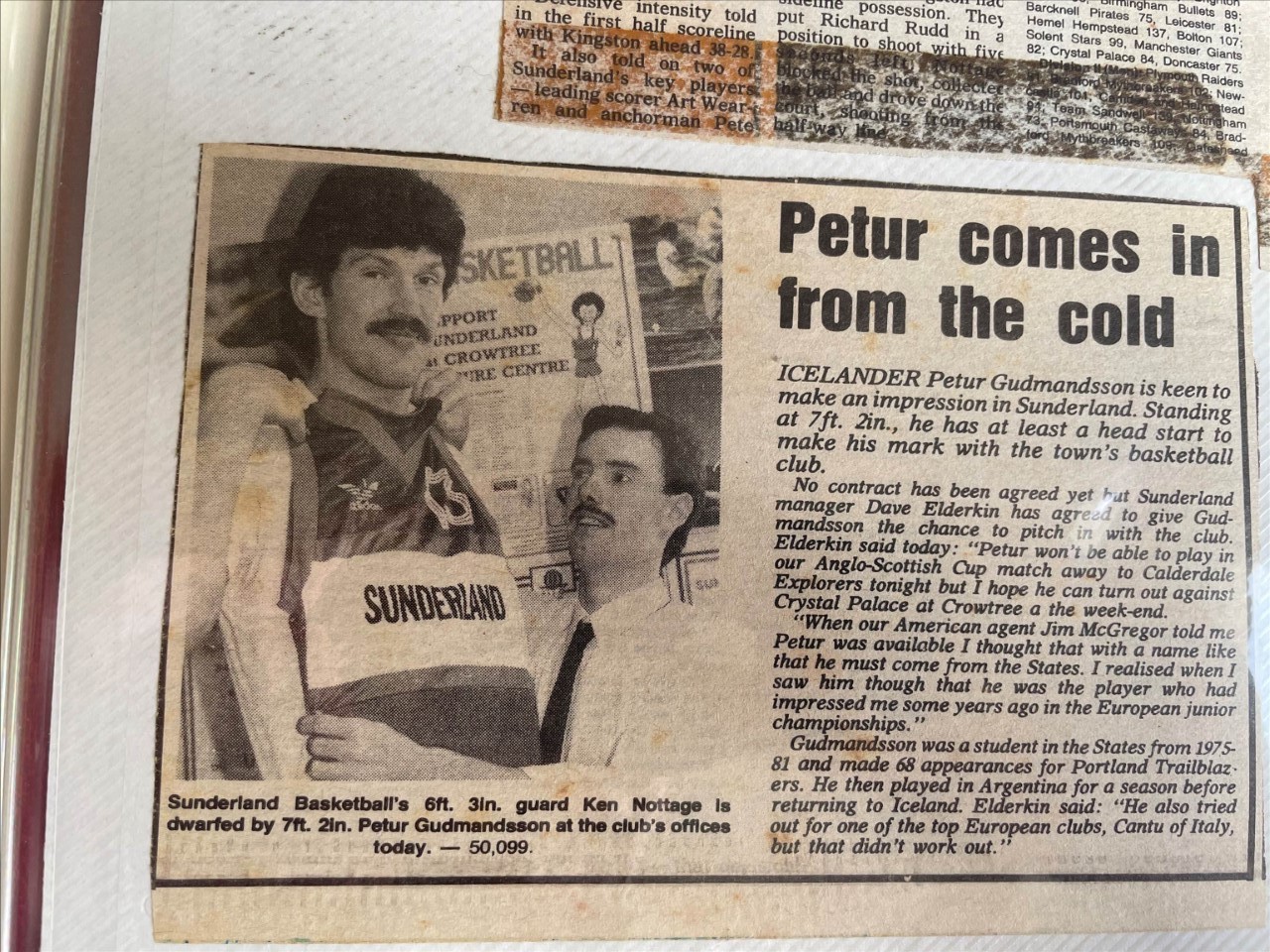

One of the key players of the 1983 squad, and now a part-owner of the Eagles, Ken Nottage looks back on his time in Sunderland, recalling how the club rose to prominence and eventually left the city behind, and the crucial influence of the financials behind the game then and now.

Perhaps most importantly Ken addresses the question ‘Will professional basketball ever return to Sunderland?’

KEN NOTTAGE’S decision to move to the North East from the other end of the country came with a huge financial risk, giving up a promising career as an engineer to chase his basketball dreams.

“To my mother’s horror, I decided to give up engineering and go up there”, Nottage remembered.

“I’d completely knackered my career, having had this job which I then dumped – but I had a good time. I did my degree, won championships, played in Europe, and I got to play for England.”

Despite being part of a winning team, it didn’t reflect in the salaries offered within the then-fledgling sport, as he recalled.

“There wasn’t much money in basketball. To give you an idea [of how things were at the time], at 23 I was the highest-paid English player and that was just below the average working man’s wage.”

Much of the early success (and what eventually contributed to the club’s downfall in Sunderland), hinged on sponsorships and the popularity of lottery tickets.

Things peaked for Nottage and the team in 1983, when the club managed to upset Crystal Palace in the play-off final.

It could have ended very differently, though.

A rivalry had begun to brew between the two sides, and Nottage’s previous affiliations with Palace in his junior days didn’t help matters.

Many teams at the time relied heavily on overseas players, but Sunderland’s backbone was built on two of their English guards – and a friendship dating back to the ‘70s.

“Jimmy [McCauley] called me and told me that the coach wanted me to come up and play for him”, Nottage said.

“At that time you were only allowed two American players, and one dual-national. So if you could get decent English players, that put you above the rest.

“Most teams would use one of their American slots on a guard, and the other on a big [centre], but Sunderland had an English pair of guards – myself and Jim.

“As we were great mates who knew each other very well and lived together, it was like telepathy on the court.

“Teams who had started to get money then looked to recruit us as a pair – they didn’t want just one of us.”

That didn’t mean that Sunderland didn’t recruit American players of a high calibre, though, including a former NBA draft pick.

Sunderland also managed to obtain the services of 7ft 2ins centre Petur Gudmundsson the following year, 1984.

Gudmundsson was the first Icelander to play in the league when he was selected by the Portland Trailblazers in the 1981 draft.

After leaving the team, he would enjoy a brief spell with the Magic Johnson and Kareem Abdul Jabaar-led Los Angeles Lakers, as well as the San Antonio Spurs.

With the city’s football team undergoing tough times, basketball began to grow in popularity thanks to their performances on the court, as Nottage recalls.

“We played at a place called Crowtree Leisure Centre, the biggest leisure centre in Sunderland, right in the town centre.

“It used to attract two million visitors a year. You could get 1,600, maybe 1,800 in there for a game, and it was sold out every game.”

However, as revenue through the club’s once-successful public lottery started to drop, sponsorships also dried up.

Nottage ended up leaving the team to play for the Southampton-based Solent Stars.

When he returned, the club was in dire straits, so much so that Nottage was asked to become a scorer, a role he’d never played in his previous stint with the team.

His scoring explosion ultimately wasn’t enough, though, with the club undergoing a slew of losing seasons.

This led to the then-owner Dave Elderkin moving the team to Newcastle in 1995, renaming them the Comets.

Money makes the world go around – and the ball bounce

BASKETBALL teams are no strangers to relocation – a phenomenon which may seem odd to many British sports fans but is familiar in America.

Perhaps the best example would be the relocation of the Seattle Supersonics to Oklahoma City in 2008.

The Sonics had been denied their second NBA championship just 12 years earlier, thanks to Michael Jordan and the historic 1995-1996 Chicago Bulls.

In 1995, it had been just 12 years since Sunderland’s triumphant victory over Crystal Palace.

The Sonics had several winning seasons over the course of the next decade, and even made the Western Conference semi-finals as late as 2005.

By 2007 though, the team had been sold, and behind the scenes, ownership was planning for relocation of the franchise.

They had missed the play-offs for two consecutive years, mostly due to the new owners’ decision to strip the team of it’s assets (including trading away star player Ray Allen) – presumably to drive fans away.

By going from a middling team to a downright awful one, the team would have better chance of landing at the top of the draft lottery – increasing the possibility of getting star players for the new fans, while also pushing their current ones out the door.

Their poor performance landed them top picks in the 2007 and 2008 drafts, which they used to acquire two future Most Valuable Players (MVP), in Kevin Durant and Russell Westbrook.

The following year, the now-Oklahoma City Thunder’s poor record meant they placed third in that years’ draft, allowing the club to select yet another future MVP, James Harden.

2012 saw the young team make the NBA finals where they were defeated by Lebron James and the Miami Heat.

Today, none of the three players ply their trade in Oklahoma, but only after several winning seasons and deep play-off runs.

The two relocations bear an uncanny resemblance.

Both teams’ departures from their cities ultimately came down to money – to ensure the team stayed in Seattle, new owner – Oklahoman-born Clay Bennett – wanted to build a largely government-funded $500million stadium – which was seen as a preposterous proposal.

Meanwhile, Sunderland’s team had arena complications of their own, eventually moving back to Washington, where the club had played their inaugural season, in addition to their struggles in putting out a competitive, entertaining team.

Since their respective moves, both teams have seen an extended period of success – with Oklahoma having a positive-winning record every year since 2010, and the Eagles becoming a British basketball dynasty.

The year after the Sunderland team’s relocation, 1996, former Newcastle United FC owner Sir John Hall bought the team, as part of an ambitious project to build a sporting club in Newcastle, similar to those of clubs in Europe, like Real Madrid and Barcelona.

Hall also bought the hugely successful Durham Wasps ice hockey team, and the rugby club now known as the Newcastle Falcons.

Nottage was unimpressed with the move to Tyneside.

“I never really thought that [the relocation] was a good thing,” he said.

“I think I played one year there, but things just weren’t the same, so I thought ‘I’m 36 now, I’ve had enough’.”

Ironically, after he’d left to work at Sunderland University, Nottage was offered the chance to run the basketball club and shortly after found himself chief executive of Hall’s grand project.

“On my first day at work I got a call telling me I needed to be in the boardroom at nine o’clock the next morning”, he said.

“I thought that something had gone wrong. They told me that they’d sacked the guy they hired for the position – he hadn’t even started working yet.

“Then they asked me if I’d like the job, and within months of working for them, I was running seven of their companies.”

Hall’s ambitious plan for a Newcastle sporting giant was largely a failure, and Nottage was given the task of finding buyers for the recently-acquired clubs.

“I managed to find a buyer for the rugby club, and the ice hockey club kind of moved away and ran itself,” Nottage commented.

“Then they asked me if I wanted the basketball club – that they’d sort the legal things and I’d just have to take it on.

“I told them I wasn’t going to do that, but I would find someone who could, so I recruited the current majority owner, Paul Blake.”

Nottage had been offered a position at Gloucester Rugby Club, and wanted to recoup the earnings he’d given up playing professional basketball, but today maintains a 26% stake in the Eagles, due to constitutional reasons.

Now, the team play their home matches in the newly-built 3,000-capacity Eagles Community Arena, allowing Blake to fulfil a 10-year ambition.

Regardless of the Eagles’ success on and off the court, Nottage feels British basketball as a whole has missed its opportunity to become a leading UK sport.

“As a sport, basketball had a real chance in the 80s,” he said.

“Channel Four was new, and it decided that it was going to have basketball on there at 7:30 on a Monday night, but they didn’t know how to do it.

“Now, you look at BT and Sky Sports – it’s fantastic. Their cameramen get right into the action, and you can see 17 different views.

“Things weren’t as good back then.”

While the move to Newcastle robbed Sunderland of its team, Nottage reflects on the fact that it was struggling to survive on Wearside, as fans turned away from a team struggling to win and took their money with them…

And he cannot see the team returning any time soon – nor does he anticipate a new club being formed.

“I don’t see the Newcastle team moving back, because they have a perfect venue in Newcastle”, Nottage said.

“It would take a lot of money to establish a premiership team.

“Just the licence is £250,000 and you need to prove that you have the business plan to operate a club.

“You need the best part of £1m per year to run a decent club, so it’s unlikely. Maybe in a league below.”

Even though the glory days of Sunderland basketball are almost 40 years in the past and seem unlikely to return any time soon, Nottage is still a familiar face to those with memories of the once local heroes…